Interview with Laurel Parker

DT: How were you introduced to the field of bookbinding?

LP: When I was in art school there was a class— that had been started a few years before— called “artist books.” It was a class that was started by one of the photo professors. The class was linked with the Mac Lab—Macs were new at the time—where we could learn Quarkxpress and Photoshop. They also had an offset press so there was some edition work being done. I took the class actually after I graduated because I was working at school and I could take a free class. This class was taught by two people: Anne Pelican, who did book restoration at the Boston Athenaeum, and Peter Madden who’s a book artist in Boston. They would trade off every week: Ann would do technical, actual bookbinding techniques, and Peter would show artist books and talk about how to put visual content into the work. But it was all very crafty. I didn’t really learn about the history of the modern artists’ book like Sol LeWitt and all of the artists in the 60s that started using the book as an art form. I didn’t learn about that until many years after art school. I didn’t even know all of that existed. So I kind of came into bookbinding from this crafty end like what they do at the Center for Book Arts in New York.

DT: When you were in art school did you know what you’d do after?

LP: No. Before going to the Museum School I wanted to study graphic design. Then I just ended up at the Museum School so I explored so many different things because it is an open place that encourages creativity. It didn’t hit me until the end: “gosh how am I going to live?” I think I knew I didn’t have what it takes to be a contemporary visual artist because I liked making things but I didn’t really have something to say myself; you have to have something to say. It’s not just about making beautiful things. Like a lot of people that go to the Museum School, when you get out you have to figure out how to make a living. I floated for a while. I took a letterpress printing class at the Center for Book Arts in New York taught by a woman who had a print shop and bindery; it was the first time that I had met someone that made a living doing something like that. I asked her, “Do you really make a living doing this?” and she answered me as I would answer to someone now which is, “Well you know, what an insulting question. Of course I do.”

DT: Actually, that’s the most common question that I hear! When I am at school at AAB whenever someone that is not a bookbinder sees one of the students that’s the first thing they say. I even hear if from conservationists and library people.

LP: Well, there are a lot of people that do this craft/job that do it just as a hobby or they have other means. You see that a lot in France. People that have family money or they’re married to somebody wealthy. Or they’re teaching bookbinding because they don’t really have to have enough clients to make a living from it. There is a lot of that because it’s not a craft where you can make a lot of money. It’s really hard to make your living. So that’s kind of an honest question in some ways. But that was the first time I had seen somebody that could do it and I thought, “Okay how am I going to do this then?” I thought about going to the North Bennet Street School in Boston but that’s more restoration work and restoration didn’t really interest me. Also I didn’t want to pay for more school, so I just kind of learned on the sly.

DT: Did you learn a lot from your experience at the Center for Book Arts?

LP: I took classes at the Center for Book Arts when I was in Boston. I would take the bus and stay at a friend’s house. When I moved to New York I was in a couple with someone, a photographer, who worked at Polaroid on their large format camera, the 40 x 80” camera. The camera was bought by an artist because Polaroid was having a lot of problems. It was moved to New York and we went with it. I hadn’t worked for Polaroid but when the camera became independent f rom Polaroid, I was asked to manage the studio. It was a rental studio, and we worked mostly with the owner because it was very expensive to rent. This artist started making a lot of really large Polaroid transfers; we did thousands of these and had a lot of assistance in the studio. He started making artist books also. Because I was already working as a freelance bookbinder—I was teaching at that point at the Center for Book Arts—I started making books for him, artist books. It was the first time that I really did that for somebody else. I learned so much in that studio. That’s also what got me to France because that artist had a studio here. Then I just started working for other people. That’s kind of the short story.

DT: At that time, you were fairly certain you wanted to focus on bookbinding?

LP: Yes. When I made films it was always so difficult. It was before people worked in video. To make films you had to have so much stuff, so much equipment. Bookbinding, at the time, seemed so much more simple to me. Like you could just make things with your hands. You didn’t have to have all this expensive equipment. Of course now I know you have to have all this stuff. You have to have a board shear and a press and all of that. When I started I didn’t have any of that. I liked working with my hands. I love books. I love everything about typography and page design and all of that so it just seemed to check so many boxes of things that I liked. So I was just looking for a way to have my own studio to make that happen. It’s worked for me in France.

DT: What do you enjoy most about what you do?

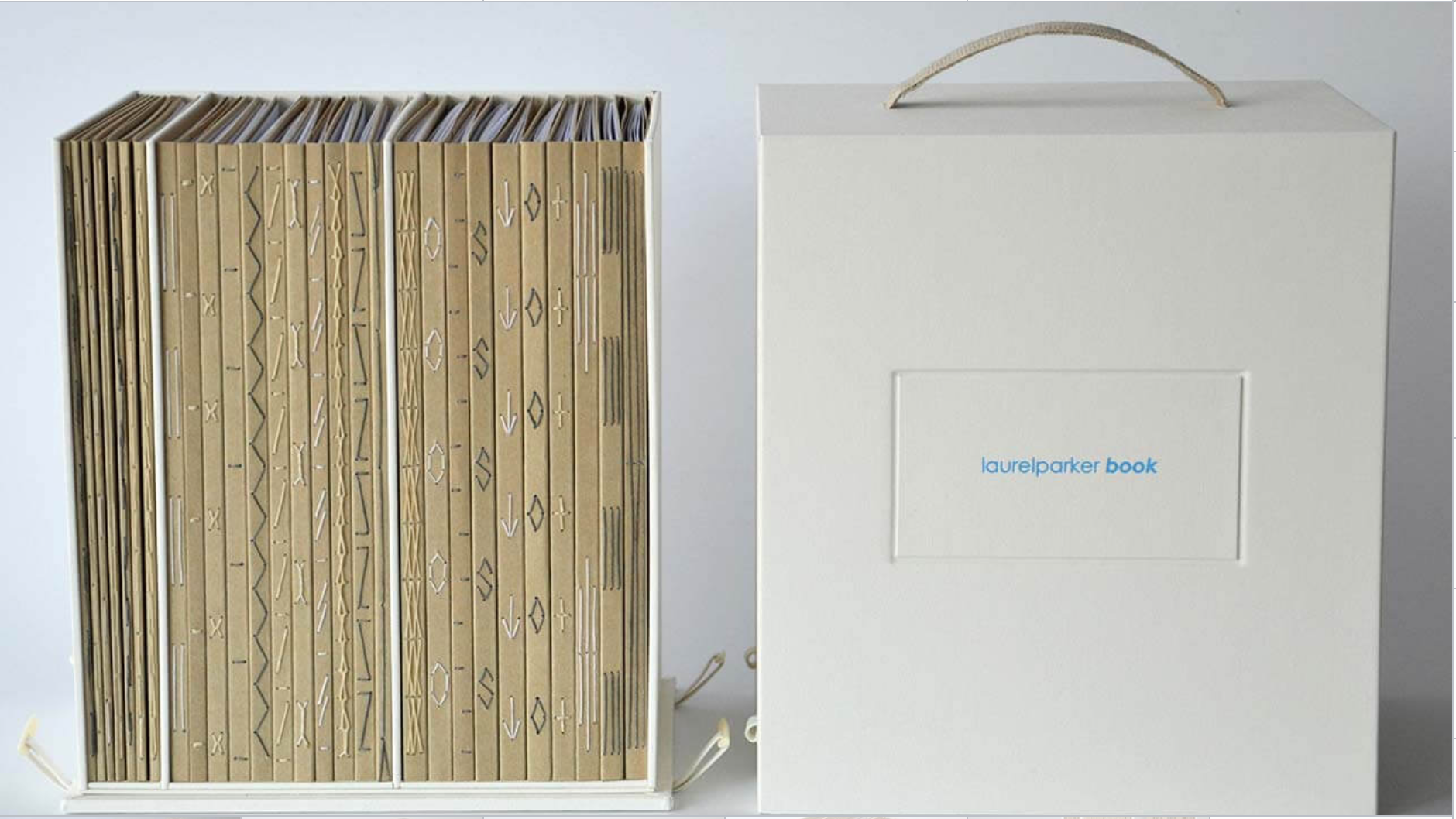

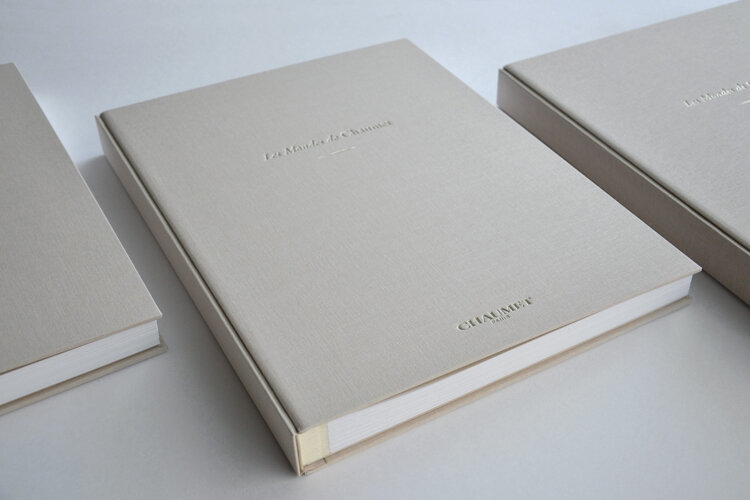

LP: I noticed on your questions you asked about the percentage of time that you actually make stuff, and we were laughing about that today here in the studio. Because actually what I like to do is design things. It’s never interested me to just make things repetitively all the time. I worked for a very short time at a traditional bindery in Boston, and I absolutely hated it. Just making the same thing over and over and over and over was just horrible. I hated it. They had maybe five different colors of leather and 10 different kinds of marbled papers and that was it. No one ever thought to propose something different. I thought, “This is just horrible; what a horrible way to go about things.” They did really good work, but the design never mattered. In our studio, everything we do is different. It’s a much more expensive way to work, but it’s custom work that’s our niche, 100% custom made. I try just out of sheer boredom to make every project different. We’ve gotten to a point where we do a lot of edition work. We do the design work in-house and make a point of saying on our website that we do design and fabrication. It’s not just fabrication. People would think that all the design stuff just pops out of your head and it’s free. I realized that we had to talk about that. We do design work like a graphic designer, like anyone else. It starts with the design and so that’s the part that really interests me is designing the work.

DT: Is there a technique that specifically interests you?

LP: We try to use as much modern technology as possible so we do a lot of work with CNC machines (creasing and cutting machines), digital cutting, laser cutting. I think what interests me the most is trying to work with industrial techniques like die cutting. Working with mechanized systems—which actually makes for a cleaner product in some ways—adapting those things to small series is really interesting to us.

DT: Do you have that equipment in your studio or do you outsource that?

LP: Our studio’s not very big. We don’t have a lot of equipment: a board shear, a large standing press, and lots of little tools. We work with other studios that have these machines. We create the digital file that’s then going to be used.

DT: Do you still take classes yourself?

LP: I took a class at the École du Louvre last year. It was a year-long class about different arts and crafts: bronze casting, tapestries, Greek ceramics, and that kind of thing. It was fascinating, and all that stuff feeds into my work. But as far as techniques, we learn on the job. Whatever I can learn on the job is always much more fascinating than anything I can take in a technical bookbinding class.

DT: Do you have a process that you design each of your pieces by or do you approach each job in a different way?

LP: It depends on what it is. But if it’s an artist book project, I meet with the client (either the artist, publisher, or gallery) and start a collaborative process. I feel like what I learned at The Museum School has carried me through my whole professional life. At school I would collaborate with friends on films or installations. I feel like that’s how I still work. So each time I make a piece I know that the artist has the concept, and I have to somehow put myself in his or her shoes to make the piece as if I were him or her. So that’s how the process starts. Definitely there are certain steps: we develop a prototype, sometimes there’s a second prototype, and then we go into the fabrication of the series.

DT: Can you tell me a little about how your studio operates?

LP: Well there’s Paul and me. Paul started as my intern when he was in school (he’s 18 years younger than I am) and he was wonderful. I told him as soon as he got out of school to contact me, and then he started working for me. He’s been full-time with me for seven years. He started off as my assistant. He learned very quickly. Then over the years he’s become better at hand work than I am. He develops all kinds of nifty techniques. Now he’s becoming a partner in the studio. He’s going to be 20% partner. We are the main structure.

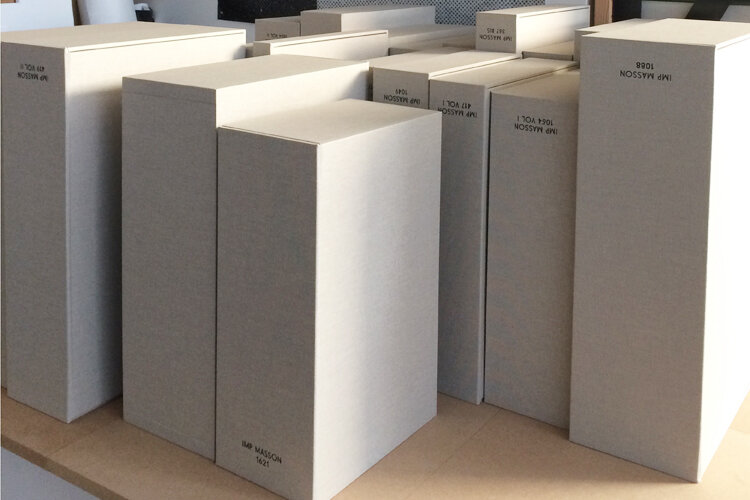

I do most the design work alone, but Paul participates more and more. I usually make the prototypes. I also handle all the clients, attend meetings, find work, and manage the business (estimates, accounting, all that). I handle the orders, set up the projects and Paul handles the production. Certain projects I handle the whole thing myself, like small artist book projects if there are around 10 copies, but it’s rare that Paul isn’t in on the project. Paul’s mostly on boxes and portfolio books. We also have a third person now who is full-time, Léa. She went to two different bookbinding schools. She’s our technician and so she does production all day also. Sometimes we have a fourth person if the job is really big. So that’s where we’re at now.

DT: That’s a lot! That’s good.

LP: I was thinking about what I was going to tell you and I think working alone is very difficult because you never advance. You spend so much time doing the business work and hustling to find clients, doing design work, and then you have to make the stuff. While you’re making the stuff you can’t get the next job ready. Then you always have holes in your calendar where you’re not working and so you never have a steady cash flow. It’s always really hard and you work like 60 hours a week. I did that for years and then when Paul came to work for me we could take bigger jobs. We could also do physically larger objects than one person can make alone. Having a third person really frees me up to find work and keep the machine going, but the sacrifice is that I’m not working with my hands every day.

DT: Do you miss that?

LP: Yes I do. If you’re not working with your hands you’re not used to things anymore, you work slower, you’re not as efficient. But somebody has to do all the other stuff too. The dream is to have a secretary [laughs]. I don’t think that’ll ever happen.

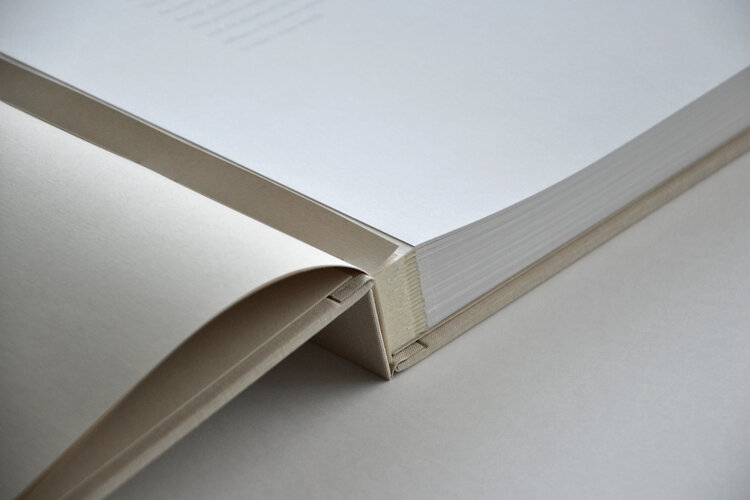

DT: How does having a team effect the work itself? You are not alone in the studio figuring things out. You can collaborate and build off each other’s ideas. LP: It’s very important. We have a lot of mottos here. One of our mottos is, “slow is fast.” We really do always take our time to not have any mistakes because mistakes are expensive. That’s very important to us that everything is slow, it’s studied. We’re always sure of what we’re doing to not make mistakes. That’s very important but another thing is that we discuss things.

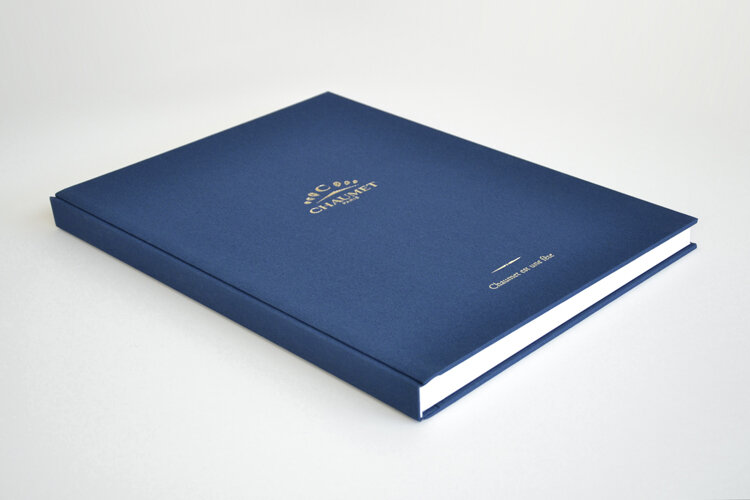

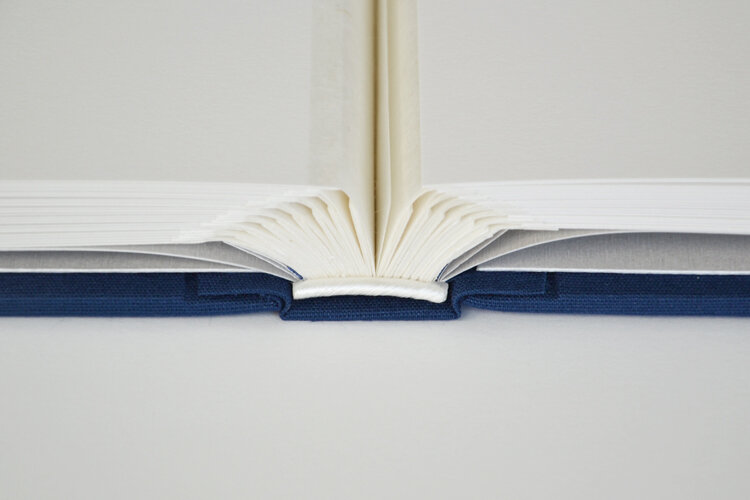

Just today we had a pow wow, the three of us. We’re making these albums for a jewelry company to show their high-end jewelry collections every year. They’re tab bindings: the tab is glued-on to each drawing and then it’s folded and sewn. You have to have compensation on the spine side for the extra thickness of the tabs, and we’ve been talking about this for like five days. In each section, are we putting three compensation tabs or are we putting four? We’re always talking in micromillimeters. Today was the first day we were sewing the album so we sewed one and Léa said, “Laurel can you come see because I’m not sure if it’s right?” So I looked and I said, “I think it’s okay but I’m not sure.” I said, “Paul, come see.” Paul was like, “I think it’s okay.” I could see we both had hesitation so I said, “Maybe we could take out a couple of tabs.” Paul agreed. We figured taking six tabs out of the whole album would be right. We’re talking about one and a half millimeters here. This conversation took five minutes and it was solved I feel like we all had a doubt, and it was good that we could discuss it. If I was alone it would have worried me, and I wouldn’t have done it right. I would have been worried for a week, but the three of us found a solution in five minutes!

DT: I saw on your website that you still teach workshops. What do you teach?

LP: I teach in art schools mostly to either graphic design students or photo students. The workshops are about book editions. The idea is that students, after school, are going to be either working as graphic designers who will do print editions or photographers who will maybe be making books as artists later on. I teach finding the visual concept of the book and how books are made. It’s going back to how I learned in The Museum School in a way but even more about the design end. In a 4-day workshop I will do three or four really fast prototypes where they’ll learn how to do a one-section binding, a Japanese binding, maybe an accordion, and maybe a perfect binding. But they’re not just learning binding techniques. I ask them “Why would you choose a Japanese binding with a fold at the right side of the book? Why would you choose that as opposed to a regular binding, a western-style binding?” There’s a reason for choosing these things and it’s not just because it’s different or it’s fun. Visually, there’s a reason for choosing things like this in designing a book. So these are the kinds of workshops that I do. When I taught at the Center for Book Arts I really liked that there was an eclectic group of people that would come to the Center. I would have a lot of professionals that would come to take classes and I really enjoyed that. There’s nothing like that in France. I tried to find adults that would want to learn on the weekend, but I would just get a lot of bored housewives that wanted to make Christmas gifts, and it didn’t interest me. I wanted to work with people like the ones that came to the Center for Book Arts. They wanted to either make book arts their life or make art, to use the book as an art form and not just as a trinket or something to pass the time.

DT: Maybe this isn’t true, but I’ve always believed that in Europe people had more of a connection to what books can be. Most of the teachers that I study with were trained in Europe (France, England, Germany). When I was traveling in Italy you see actual studios where people make books, where as in the U.S. it’s very rare.

LP: I feel like in Europe it’s all very classical book binding. We talked about this in the studio today. I never say that I’m a bookbinder, ever, and neither does Paul.

DT: Because you’re not a fine binder?

LP: Right, and what is fine binding? All these things come down to is doing a 19th-century- style binding. Like in France: sunken chords with a tube on the spine and a leather binding. That’s a very classic a way to bind a book but there are so many other ways to bind a book. So you’ve got these two polarities: either just industrial binding (mostly glued spine, perfect binding or smythe sewn square back, industrial) or there’s the fine binding (very long and laborious and not adapted to everything).

DT: Would you say bookbinding / book arts are more prevalent in the U.S. or Europe?

LP: When you say “bookbinding” in France people immediately think of books sewn on cords and covered in leather with gilding on the spine or restoration work. On the flip side of that, in America you have a lot of exposed spine bindings—really crafty—which all comes from Keith Smith, the whole 80s bookbinding revival. In America you had traditional bookbinding that kind of died in the 50s and 60s. Then there was a revival with hippies making paper and making books. It was completely parallel to artist books from the 60s and 70s. People like Sol Lewitt and Ed Ruscha. All those were industrial bound books. You have these two different worlds of bookbinding that never meet, they never crossover, and they hate each other. It just seems so stupid to me because every time I do a book project with someone I never think, “Well it has to be made by hand.” I always think, “Well what is the concept that the artist wants to do and how we going to make it?” If there’s something that can be or should be mechanized, or if it’s part of the concept, then we will. If it’s something you can only do by hand, then we’ll do it by hand. We don’t only do it by hand because, “it must be done by hand.” It just seems silly to me. It’s the same thing with printing. If a book calls for offset printing then it will be printed offset, but if it calls for letterpress then we’ll do letterpress. There are reasons for doing one or the other. For us the first reason is always conceptual and the second is aesthetic.

DT: How did you find your niche with artists and book publishers and how long did it take you to become established?

LP: It was very long. When I was in Boston I worked at Paper Source. That was the only opening that I had, so everything was about functional stuff like albums and journals. Then when I was in New York working for an artist, I discovered what I really wanted to do. When I moved to France that was my goal. I didn’t know it would take so long but it took a few years. I had a really good opening. Do you know the French bookbinder Sün Evrard? I’d met her and we kind of became friends. A book publisher contacted her for a job and she said, “Well I’m not the person for this but I know someone that is.” That kind of opened that world to me. Then you do one and another and another. It took a few years to become known, it took a while. I have to say the first two years I had a partner in business who didn’t share the same vision, and things didn’t go anywhere. Then I went into an incubator program for two years, by myself. I took accounting classes and business classes and all that. During that time I was trying to get clients, and then it took me another few years. So it’s maybe six or seven years. I’ve been here for 15 years, so the first six or seven years were really hard, really hard.

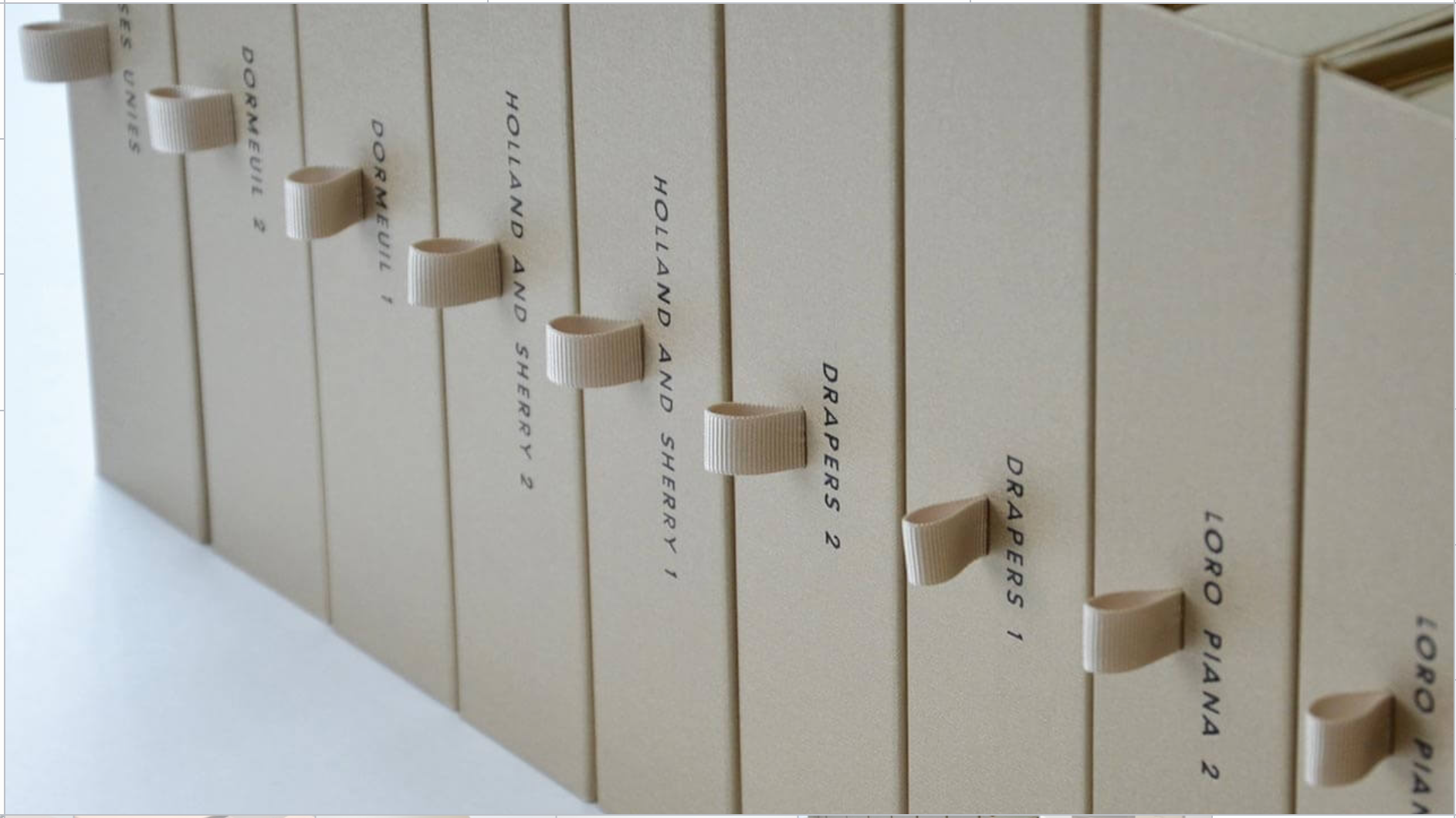

I can put our clients into four categories: everything surrounding artist books (artists, galleries, artist book publishers), photographers looking for a portfolio (so that’s a functional item but it needs to be designed every time), libraries and institutions looking for conservation boxes and jewelry and fashion houses needing albums and boxes to present their work in.

DT: Do the jewelry houses present pictures of their work or the actual jewelry?

LP: High-end jewelry is always presented as a drawing. We worked a lot with Louis Vuitton on special editions. For Hermes we did really beautiful handmade menus for a special meal, for like billionaires. Anything that’s around special paper things that need to be made by hand. Those are our four main groups of clients, and getting into each one of those groups has been long and difficult in it’s own different way. Working with artists was the hardest one because the world of contemporary art is very snobby and clicky. That’s been hard to bust into. At the beginning I would go to art fairs and give out my business card and give brochures and everybody would look at me like I was a loser [laughs]. That took a really long time. They’re the kind of people where the more you’re nice and friendly the less they like you. So you know, I’ve had to cultivate this whole thing of being like, I don’t care, and then it seems like they’re more interested. Which is really weird.

I’ve worked really hard at trying to get my foot in the door, but you can’t just call people cold turkey. You have to get introduced by someone, like a distributor. The company that sells book cloth to us got me into Louis Vuitton at the beginning. They said, “We know this girl. She does really great work.” So that helps out a lot. You can’t just call up people and say “I’m a bookbinder, and I make really great work.” It always go through somebody else. And then I really put in the work. I go visit them. I go with a lot of work. I put on my best coat and best shoes and do my song and dance.

DT: Do you like that part of it?

LP: I do actually. Because you have to seduce them; you have to make them believe in you. I think it really works for me that I’m foreign; I’m an American. So it’s charming for them. I do have a different aesthetic than what they see here. Some people do copy us now, but I think I was the only one that was doing stuff like that when I started.

DT: That takes a certain personality to keep with it. Do you have a mentor or someone that you model your career path after?

LP: I have a friend who is a letterpress printer in New York who was always really good in business. It was really good to see how she was working, but in bookbinding there wasn’t really anybody that was doing what I wanted to do. DT: How did that make you feel?

LP: It was isolating.

DT: Did you always know you could do it, and it was just a matter of going through the process? Or was it harder than that?

LP: I think the fact that I was manager of the studio in New York and.....I’ve been working since I was 14. I’ve always had a summer job and my senior year in high school I also worked evenings and weekends so I’ve always been working. I’ve always been independent. I was independent from my family since 18. I put myself through school and I’ve had so many shit jobs in my life when I was younger. I knew I wanted to be independent. I knew I wanted to have a studio of my own, and then after working in New York and running that photo studio I knew I could make something happen. That’s when I knew I could do it.

Of course then trying to do it in France. When I think back, I think that was really crazy. I didn’t speak French. I had to learn French. I had to learn how to run a business and run a business in a foreign country and all that was really, really crazy. It was really, really hard. So yeah, I think you have to have a certain stubborn personality to make that happen. For the last 15 years I’ve been with a wonderful man. We’ve been splitting up, so we’re not together anymore but we’re still friends. If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have been able to do it. It’s not that he gave me any financial help because he’s an artist also; we were both hand to mouth. But he really helped me at the beginning. Especially writing things because I was incapable of writing French in the beginning. He’s like me. He has this “We can do it” attitude. Because we’re both artists I never thought that I should be doing something like marketing or something. It just never crossed my mind. I’ve always thought it was possible. I have this capacity if I want to do something then I go full steam ahead. I’m kind of tired now I have to admit. I’m going to be 50 years old this year and I know I’m tired. This is why Paul is here. I can’t work standing up all day everyday like I used to. That’s killed me. I was doing that up until 45, 46 years old I was working everyday standing up. I had terrible pains in my legs all the time. It’s hard physically and emotionally to do that. It’s really hard.

DT: How many hours do you work a day?

LP: Well we start at 9, and then Paul and Léa leave at 6 or 7 and I usually keep working. I have a hard time stopping work. I try not to work. I try not to work weekends. For many years I worked all the time, all the time, which is probably why I’m not in a couple anymore. I don’t have children either; I didn’t have that.

DT: What aspects of running the business do you find most challenging?

LP: Sometimes the relationships. I’m always working with different people. The clients change all the time. You know you never know who you’re going to be confronted with and sometimes you just don’t like the person in front of you. Or the client is a jerk. When it runs smoothly it’s great. When I have somebody in front of me that’s just a jerk that can be really hard to handle but I try to stay as diplomatic as possible. It’s rare but sometimes you realize that you’ve got a client that’s trying to pull one over on you and that’s been the hardest thing: protecting the business. Because if we have one thing that goes wrong like that it could kill the business. It could absolutely kill it. So that’s why we’ve always got to make sure that everything is going right. That if we’re working with a printer we have to make sure that the prints have been validated, that everything’s been validated and everybody’s doing everything that they’re supposed to be doing. Those things are really hard because you’ve got to be on the ball all the time, all the time, all the time. Because if we screw up and it’s a big screw up, it can kill the business. So that’s been the hardest part and sometimes you know, you take a bullet.

A few years ago we were working with a book publisher on a fancy special edition book of lithographic prints. The printer sent prints, and I had to refuse them. I had to refuse the prints, send them back to him say, “You have to go through it cause they’re dirty, they’re badly printed, we don’t have the exact number we were supposed to have, they didn’t arrive the way they were supposed to, and you didn’t follow the contract.” I think that’s the kind of thing that if you’re a man and you’re saying those things it’s received differently than if you’re a woman saying them. So those are the kinds of things I find really hard to deal with sometimes.

DT: Do you think the possibilities within the bookbinding field are similar or different than other arts and crafts like painting, ceramics, jewelry?

LP: Well bookbinding is something functional. The book is a functional object. Which is different. Painting is a fine art. It’s completely different than bookbinding which is a craft to create something functional. A regular binding for whatever book or a decorative binding or an album, portfolio or box—these are functional items. Then it becomes something else when it’s used by an artist as a medium. As if it were a painting or a film or a sculpture. When it’s used in this context it becomes something else.

I think there will always be a future, and I think the bookbinder has to adapt. I think that’s been something really difficult for bookbinders in France. Because the bookbinding schools only teach fine, 19th-century-style binding, which there is almost no work for anymore. I mean there is more work for it in France than there is in America because you do still have people that will go to a binder to rebind a book for his or her personal library. But it’s mostly older people and they’re dying off and younger people prefer to buy a new car or go on vacation. Even if you wanted to do 19th-century binding you need to adapt and use that for restoration or know that your only going to have very rich clients and very few. So either you stay with that or your adapt. So for us we’ve adapted because I’ve never been interested in doing fine binding, never. And also I think instinctively I just knew there’s no work for it. There’s no future when you think about the money you have to make to pay yourself a correct salary. I’ve been doing this for 15 years in France, and I’m still not earning a decent salary. You have to pay yourself a decent salary, and pay your taxes and social security charges, and pay the rent, and all the bills, and subcontracted work, and buy all the materials that make the studio run. It’s a huge amount of money, so you can’t just make little leather bindings for little old ladies that want to pay 80 euros for a binding that’s going to take you eight hours to make. You can’t do it.

DT: Do you see that market growing or changing?

LP: We haven’t gone after that market. It’s not even in my genes to do something like that, that style. But it is there. I do know people that do that, that want to do decorative bindings, decorative fine bindings, design bindings. That does exist in France. There are so few clients for that kind of thing. So much of that style stays in the 19th century. I just don’t understand it. It’s not even modernized in any way. It just really frustrates me sometimes. I feel like I’ve just seen the same book over and over and over.

There was a wonderful bookbinder, retired now, Jean De Gonet. I don’t know if you know his work. He’s like the French god of modern bookbinding. He did all these amazing things based on bindings from the middle ages with exposed raised cords, but he would use molded plastic boards instead of wooden boards. He’s like the only one that came up with anything different and modern and new. And Sün Evrard, who has done some very interesting things especially in conservation bindings. She’s really done some incredible things—structures without paste and glue, parchment bindings for restoration. Those are the only two who have gone beyond the classic French book that you can’t even open. It’s just to look good on the shelf.

DT: Where do you see yourself in five years?

LP: We’ve been bemoaning the fact that we see less and less of the type of artist book projects that we like to do. And it’s because there is no money out there so publishers get squeamish about doing stuff like that. Then it just hit me one day, “Well why don’t we just do it ourselves.” Now we have the contacts: we know artists. What else do we need? So this is the new project, but it means that we need to finance things. The idea is that if we do have a little profit instead of watching it go into taxes—because that’s what happens—we will auto-finance artist book projects. So this is the new thing, and I’m keeping my fingers crossed. I think it’s a good idea.

DT: It’s exciting to have a new thing to work on when you’ve been at the same thing for awhile.

LP: It’s good to have a project. I mean some people just want to do the same thing because they don’t want too much excitement or to be too stressed out, and I kind of feed off of that. So this is the new direction for us. Because I think... we’re always joking here, “If I make another portfolio book I’m just gonna kill somebody because I just can’t do it anymore” [laughs].

DT: What advice you’d give to a young binder just starting out?

LP: I think it would be to think about how a book would be used in the here and now and to not think about reviving something from some kind of murky past. I mean if someone decides to be a doctor they don’t start thinking about putting leeches on peoples backs and perform operations in a theater. I’m not saying that I don’t think we should look to the past for structures, because I do. I look a lot. I study a lot about the history of bookbinding and how those things can be used. I’m talking about asking what are the modern day applications. Because if you have to make a living—you have no other source of income except what you make—then you have to be intelligent about it. You have to think, “How can this be applied today in 2018?” If it is traditional bindings then where are your clients? If you think you want to do traditional bindings, then make sure you have the clients. That’s what I would say. Just be smart about it business-wise. Even artists, I know that was kind of like the taboo in art school, to talk about money. But every contemporary artist that has succeeded has been a good businessman also. If you’re not independently wealthy, you have to think about how you are going to make money doing it and do it well.

DT: Do you think if it was more socially acceptable to talk about money, we’d learn more from each other about what works and what doesn’t work?

LP: Well, I remember I had a very strange experience at the Center for Book Arts. They had a round table where we were going to talk about how we priced our work. How do you come up with our quotes, your estimates? Which was a great idea. I talked about how I priced out my work: “Okay you calculate. What are the materials for the job? If you need 80 sheets of whatever then you add 20% of loss because you will always have mistakes. Then you calculate your time to make those 80 things but you will have loss there...” Standard business stuff. Then, this other bookbinder who was a teacher at the Center for Book Arts said, “Wait a minute you’re making people pay for your mistakes?” And I thought, “Well geez I’m not a robot.” Nobody can work 100 percent of the time perfectly; you have days where you’re tired, days where you’re sick. It seemed so strange to me. You can take any business or economics class and it’s standard stuff. It ended up in an argument, this round table, and I just thought that was so stupid.

You take any other profession like doctors, lawyers, or psychiatrists: these people are not ashamed to talk about what they’re charging. Lawyers have no problems saying that it costs x number of dollars for 15 minutes. They have no problems with that. You call them up on the phone and they note the time you spent with them on the phone. So why should I act like what I’m doing is for the betterment of the planet or because I’m a saint? It’s business. Just because I love what I do doesn’t mean I need to suffer. Not to say I’m making gobs of money, but what I’m saying is that you need to approach your work as a business, because that’s what it is and not be ashamed about what you are charging. If you need to explain this to people then you do. And that’s part of the job too. I have to explain to my clients, many times, why something costs x amount. I say, “Well this is how much time we’re going to pass and these are really good materials we’re using.” I know the value of what we’re doing. I’ve been doing it for so long I know what it costs. If we charge any less then the studio closes so this is what it costs.

I think there is something in arts and crafts, like well it’s just a hobby. Well no, it’s not a hobby. I do this for my living. I went to school just as long as a lawyer did. I was in school for 7 years. I know a lot about art, art history, art making, art selling. I have a critical eye and those things are worth something. So I think you’re right. We shouldn’t be ashamed to talk about money. It would be better if we all did because it would help to raise our prices too. In other fields—graphic design, animation, the film industry—there are industry standards and in bookbinding there isn’t anything like that. Then you’ll have somebody working in the same town as you, and you find out that she’s charging half the price. It’s just mind-boggling. You think, “If I’m charging what I’m charging and I can’t even make a living then how can she charge half the price.”